Transferring Knowledge from Systematic Reviews to Practitioners

Researchers have few incentives to write to the general public. On the other hand, practitioners are not used to consume software engineering research. This “Two Solitude” problem is well-known, and several attempts have been made in order to remedying it.

In a study called Evidence Briefings: Towards a Medium to Transfer Knowledge from Systematic Reviews to Practitioners, published at ESEM’16, we propose and evaluate “Evidence Briefings”, a new method for dissaminating research results to practitioners. This model is inspired by the “Rapid Reviews”, a well-known method used in Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM). Rapid Reviews are aimed at reducing the effort of the traditional systematic reviews by provididing brief documents with few pages focusing only on the main findings that are useful to practice. More interestingly, however, is the fact that Rapid Reviews are gaining attention lately. Among 100 rapid reviews published between 1997 and 2013, 51% of them were published between 2009 and 2012.

Differently than Rapid Reviews, Evidence Briefings are an one-page document, extracted from a systematic review. It uses the principles of Information Design and Gestalt Theory. The primary objective is to develop documents that are comprehensible, accurately retrievable, natural, and as pleasant as possible.

Method

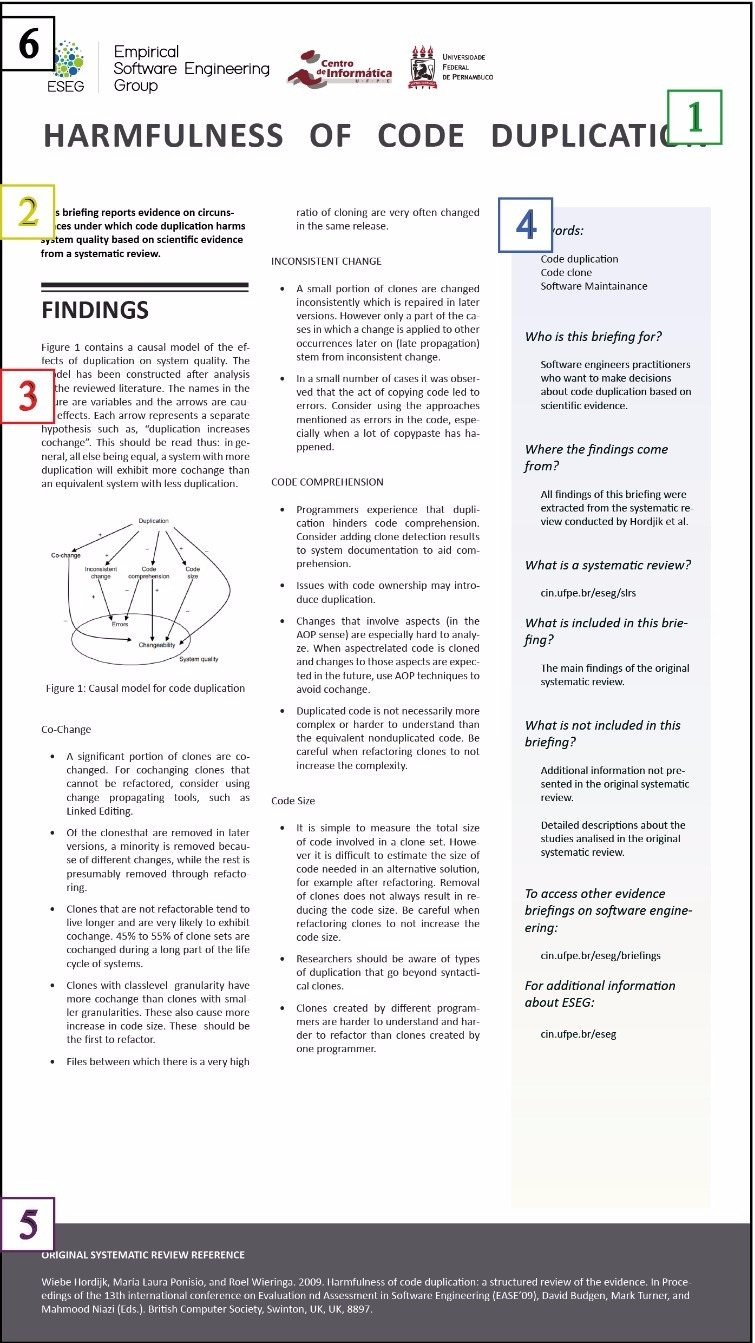

Figure below shows an example of an Evidence Briefing.

There are several design techniques applied in this briefing. Here we discuss only ot ones about the structure of the briefing (represented by the numbers within squares). They are: (1) The title of the briefing. (2) A short paragraph to present the goal of the briefing. (3) The main section that present the findings extracted from the original systematic review. (4) Informative box that outlines the intended audience and explains the nature of the briefings’ content. (5) The reference to the original systematic review. (6) The logos of our research group and university. All concepts obtained in the previous steps were analyzed and applied in an evidence template, which is open-sourced under CC-BY license.

We create Evidence Briefings to 12 representative systematic reviews that were selected in a tertiary study. All the 12 evidence briefings as well as the briefing’s template can be found in http://cin.ufpe.br/eseg/briefings.

We evaluated the evidence briefings in terms of both content and format. We used personal opinion surveys to ask researchers and practitioners what they think about evidence briefings. Our group of practitioners is composed by the authors of the systematic reviews. Our group of practitioners is composed by StackExchange users that posted questions related to the systematic review in charge.

Our sample of reseachers is composed by 7 authors that answered the questionnaire, which corresponds to 31% of the 22 invitations. Our sample of practitioners is composed by 32 StackExchange users that responded the questionnaire. This corresponds to 21.9% of the 146 invitations.

Results

In the practitioners survey, we asked six questions to evaluate the briefing’s content. Here we discuss only two of them. We start by asking “To what degree do you think the information available in the briefing we sent to you can answer your question on StackExchange?”. Among the answers, 10% said that the briefing has totally answered, and another 20% said that it has partially answered their StackExchange questions. Another 32% said that the briefing touches a related topic, but does not help to answer the question. The remaining 38% said that the briefing is not related to the question and, therefore, it does not help in answering it.

In the next question, we asked “Regardless the briefing answers or not your question, how important do you think is the research presented on the briefing?”. We found that 62% of the respondents said that the researches presented in the briefings are “Very important” or “Important”. Moreover, 25%, 6% believe they are “Moderately important” and “Slightly Important” respectively. The remaining 6% believe they are “Unwise”.

In the reseachers survey, we asked “How does the briefing cover the main find- ings of your paper?”. We found that 72% (5) of the respondents describe as “Very good” or “Good”. The remaining 28% (2) said that it is “Acceptable”. This suggests that even though we are not the authors of the research papers, we were capable of creating, at least, acceptable briefings.

In terms of format, we observed that 71% (5) of them “Strongly agree” or “Agree” that it is easy to find information in the briefings. Another 71% (5) “Strongly agree” or “Agree” that the briefing interface is clear and understandable. Finally, 56% (4) “Strongly agree” or “Agree” that the briefings look reliable.

Concluding

Our results suggest that Evidence Briefings was positively evaluated. For instance, most of the researchers and practitioners believe that it is easy to find information on Evidence Briefings. Also, most of them believe that it they clear, understandable, and reliable. We believe that Evidence Briefings can play a role on transferring knowledge from systematic reviews to practice.